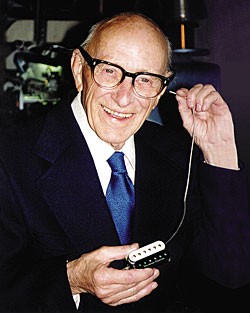

Seth Lover

Humbuckers And other Lover innovations

Who got you started on the path of electronics?

Seth Lover: I was born in Kalamazoo, Michigan, on January 1, 1910. In the early 1920s, a schoolteacher in Pennsylvania began helping me with electronics projects. I was living with my grandparents at the time, and we used to get the Philadelphia newspaper; the radio section showed how to build different circuits. I guess my first project was a one-tube radio, which worked pretty well. My grandparents had died in the 1920s, and I decided to join the Army, where I worked with electronics. And when I hit the end of my term in 1931, I took a radio course from a Washington, D.C. company. It was actually my second – the first was in 1925, while I was working on a farm.

How did your first radio business come about?

After my second course, I went into business in Kalamazoo, repairing radios and the like at the Butler Battery Shop. We’d recharge batteries, repair radios, and install them. But when Butler died, we started a shop at 465 Academy. Eddy Smith, an orchestra leader at Long Lake, was a good customer. I used to build amplifiers for them. The poor guitar player would be playing next to the piano, and you could see him moving his hands, but for the life of me you couldn’t hear him play one note! If they let him get close to the microphone, he could be amplified and heard.

In 1935, I went to work for M&T Battery, doing the same thing. Then in ’41, Walter Fuller wanted me to come to work for Gibson. They were buying amps from a Chicago company, the EH-125, the 150, and the 185. We’d plug in the tubes and test them – I was a troubleshooter. And when World War II came along, I joined the Army again.

In what capacity?

They offered me a Second Class Radioman rating, and I ended up in the Navy. I was sent to Connecticut, then to Treasure Island, near San Francisco, to radio electronics school. That August, I received my First Class rating and was sent to teach electronics near Washington, D.C. Most of my time during the war was spent teaching.

In 1944, I had to go to sea [on] the USS Columbus, which was being built in Massachusetts. I was sent there and began checking installations and spare parts, and a little later we were out to sea. Well, about 500 miles out, the drive shaft broke, and we had to turn around. In order to get at the thing, they had to cut a hole through all the decks. And before they got the darn thing fixed, the war was over!

Did you resume your electronics work?

Yes. I went back to work for Gibson and stayed for a couple years, until the Navy built a training station in Michigan. With my Chief’s rating, I was asked to work for them for $5,000 per year, which was a lot of money back then. Gibson was only paying me $3,000. A few years later, they wanted to transfer me to Minnesota. Ted McCarty asked me to build a special kind of pickup, which I did by hand. Then he decided Gibson could afford to pay me what I was getting in the Navy, so I was back with Gibson in 1952.

What were some of your earlier designs?

Before I’d gone into the Navy, I’d begun to design an amplifier. The tremolo circuit in typical amps at the time “putted” along if there was too much depth. I found a way to get a tremolo without any noise, using an optical device, and Gibson was building it while I was in the Navy. So in 1952, I began designing other amp circuits. In ’55, I got the idea for this humbucking pickup. When a single-coil pickup, got too close to an amplifier, it would make a godawful hum.

I had designed an amplifier – the Model 90 – which had a special humbucking choke, and figured I could use the same concept on the pickup itself. It was quite simple, really – just two coils opposed, and they’d pick up the hum and just cancel out. I designed it into the tone circuit of the amplifier, and if you’d swing to one end it would wipe out the bass, to the other extreme it would wipe out the treble. So, the pickup was similar in concept.

When did your humbucker actually begin production at Gibson?

We starting building our version in 1955, even though we didn’t have a patent, and that’s when they got the “PAF” stickers to put on them. When we finally were granted our patent, we changed the sticker to one with a patent number, but we actually printed the wrong number on the sticker, one that matched our tailpiece. This way people who sent away for copies of that patent didn’t ever get a copy of the pickup (laughs)! We were replacing the P-90, and there were other single coils being used, especially on steel guitars. I did make a humbucking pickup for steels that worked particularly well. The Gibson Electraharp had my pickup on it, and it was a whopper, but they didn’t build too many of them. It was quite expensive.

I bet you’ll like this. [Seth rummages through an old cabinet, and pulls out a cloth-wrapped something.] This is my PAF prototype. It has a stainless steel cover. There’s no high-conductivity in stainless like copper and brass, so it worked well. When the salesmen saw this with no adjustment screws, it was like breaking their arms! They just didn’t have anything to talk about. So, next came the punched-out holes and the adjustment screws.

Was there anything you did specifically for Epiphone?

Epiphone guitars used to have a bunch of pushbuttons, and every time you’d change settings, it’d go “clunk!” I designed a switch with a rocker panel and a magnet to hold the position. My version was never used, but it worked awfully well.

And on the Epiphone mini-humbucker, I changed the design to offset the screws and look different – maybe better in some ways – than the Gibson humbucker with its straight screws. It wasn’t quite as loud as the Gibson version, with fewer turns of the coil, and it was a bit trebly. But it did the job.

What prompted your shift from Gibson to their main competitor, Fender?

I stayed with Gibson until 1967, and then had an offer from my friend, Dick Evan, who was Fender’s chief engineer. Now, while I designed most of the amplifiers and pickups, I never did hold that title. I was just a designer. CBS had bought Fender, and they were kind enough to offer me a job. He sent me a ticket to come out [to California] and talk. And they offered me $12,000 per year. I was only getting $9,000 at Gibson.

So I came out and did design quite a bit of stuff for them. But the thing was, if the front office didn’t ask for something, they just weren’t interested in anything you’d come up with.

How did you and Seymour Duncan join forces?

After the patent ran out, Seymour started making the pickups, and he did an awfully good job, not just in appearance, but in materials and workmanship and sound. Everything, down to finest detail, was intact. We had used plain enameled #42 wire. A lot of people would use plastic-coated wire, but the results weren’t the same. We used nickel-silver on the covers originally, sometimes called German silver, again due to its low conductivity. You can’t solder stainless steel, so the nickel-silver worked better. And that’s what you see on these special Duncan-Lover pickups. It’s really faithful to the original. The SH-55 will have my stamp of approval on it, and I’ll even get a small royalty on each sale. Now, that’s something that Gibson never got around to giving me! My name doesn’t show up in too many of these history books, and maybe they didn’t value design in those days. I guess that’s why they never paid me much [a wicked glint in his eyes signals that Seth is gently pulling my leg]. I did a lot of work, and now it seems to be getting recognized.

Δεν υπάρχουν σχόλια:

Δημοσίευση σχολίου